From COVID to Ukraine: Media-Manufactured Consent

On The "Putin Apologist" Accusation

Driving home from the gym Tuesday night, I saw a billboard demanding a no-fly zone over Ukraine. This, it turns out, is now a super-majority position in America, according to a recent poll, despite the near certainty that this would lead to World War III. Another example of manufactured consent at work.

One of the ways the discourse about the Ukraine war is policed is by claiming that someone who mentions NATO expansion as one of the causes of the current conflict is a "Putin apologist". Oxford-trained British researcher Noah Carl wrote a piece refuting this lazy ad hominem charge. I have posted it in full below. Before that, a quick update on our system's top names, in light of the Ukraine crisis.

Ukraine Crisis Rewards Oil Exposure

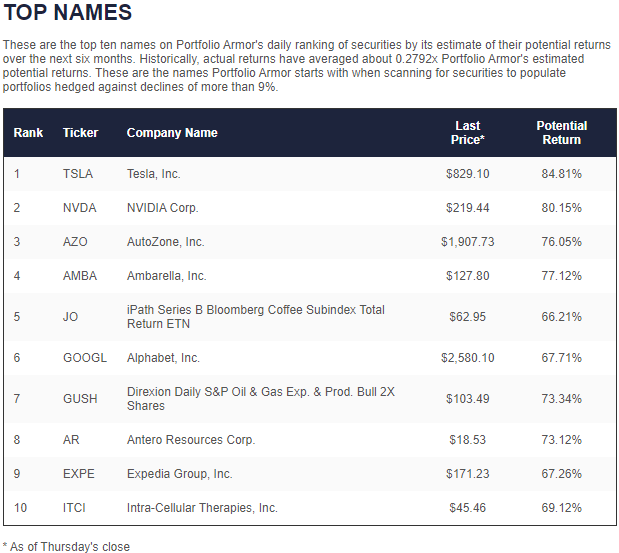

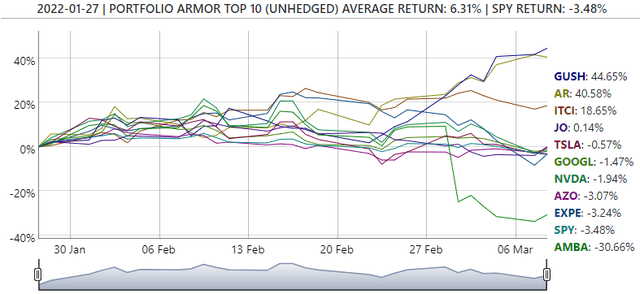

In my previous post (Ukraine Is Trying To Goad The U.S. Into World War III), I mentioned that our top ten securities on Monday included five oil names. Our system's gauges of stock and options market sentiment started picking up oil names well before Russia's invasion of Ukraine though. For example, these were our top ten names on January 27th. As you can see, they included the Direxion Daily S&P Oil & Gas Exp. & Prod. Bull 2x Shares ETF (GUSH) along with the oil E&P Antero Resources (AR).

Screen capture via Portfolio Armor on 1/27/2022.

Here's how they've done since: up 6.31%, on average, versus down 3.48% for SPY, with pretty much all of our gains coming from the two oil names plus the biotech stock Intra-Cellular Therapies (ITCI).

Now on to Dr. Noah Carl's piece.

Authored by Dr. Noah Carl at Substack

Mentioning NATO does not make you a "Putin apologist"

If you venture to suggest that NATO expansion has anything to do with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, you will be promptly informed that you’re a “Putin apologist” or that you’re peddling “pro-Putin talking points” (or some variation on this theme). The argument seems to be that, by suggesting Putin’s invasion was motivated – even in part – by anything other than bellicose revanchism, you’re absolving him of responsibility and even undermining the war effort. However, aside from being a blatant ad-hominem (most people, though not all, consider “Putin apologism” to be a bad thing), this argument is deficient on three counts.

First, foreign policy analysts have been pointing out the risks of NATO expansion since before Putin came to power. It’s therefore very difficult to see how they could have been engaging in “Putin apologism”, unless they are somehow capable of time travel. Vladimir Putin become Prime Minister of Russia in 1999, before succeeding to the Presidency the following year. Yet as far back as 1997, Jack Matlock – US ambassador to the Soviet Union – said the following in a Congressional statement:

I consider the administration’s recommendation to take new members into NATO at this time misguided. If it should be approved by the United States Senate, it may well go down in history as the most profound strategic blunder made since the end of the Cold War. Far from improving the security of the United States, its Allies, and the nations that wish to enter the Alliance, it could well encourage a chain of events that could produce the most serious security threat to this nation since the Soviet Union collapsed.

Bill Clinton’s Defence Secretary William Perry wrote in his book My Journey at the Nuclear Brink that he was so opposed to NATO enlargement in 1996 that he “considered resigning”, and that he is “not willing to concede” that the “rupture in relations with Russia would have occurred anyway”. In 1998, George Kennan – who’s been described as the “architect” of the US containment policy during the Cold War – told the journalist Thomas Friedman:

I think it is the beginning of a new cold war. I think the Russians will gradually react quite adversely and it will affect their policies. I think it is a tragic mistake. There was no reason for this whatsoever. No one was threatening anybody else. This expansion would make the Founding Fathers of this country turn over in their graves.

Second, many of those who’ve expressed reservations about NATO enlargement don’t exactly fit the mould of a “Putin apologist”. I’ve already named three – two former US ambassadors and a former defence secretary. But there are plenty of others who can scarcely be accused of having pro-Putin sympathies: former Australian Prime Minister Malcom Fraser; former US Defence Secretary Robert Gates; former British ambassador to Russia Sir Roderic Lyne; and current CIA Director William Burns. They’re all in this excellent thread by Arnaud Bertrand. Even Joe Biden warned about NATO admitting the Baltic states in 1997.

If a former US ambassador (and a patriot to boot) can describe NATO enlargement as something that “would make the Founding Fathers of this country turn over in their graves”, it is surely possible for others to reach similar conclusions without being stooges of the Kremlin. Now I’m sure there are some genuine “Putin apologists” in the West, and they may well go around blaming NATO for the present crisis. But to conclude that everyone who blames NATO is therefore engaged in “Putin apologism” would be an example of the “Hitler used toilet paper” fallacy. (“Oh, you use toilet paper? So did Hitler!”)

Third, there’s a lot of evidence that NATO enlargement was a factor – arguably the most important factor – in Putin’s decision to invade. This evidence is by no means dispositive; isolating the causes of particular historical events is notoriously tricky. But I believe it’s possible to defend statements such as, “If the West had ruled out NATO membership for Ukraine, Putin would not have invaded”. Having said that, I’m willing to be convinced that I’m wrong. Some people claim that Putin always had designs on Ukraine, and would have invaded regardless of our policy; or perhaps that the only thing that would have stopped him is Ukraine joining NATO even sooner! If so, let them make their arguments without calling those of us who disagree “Putin apologists”.

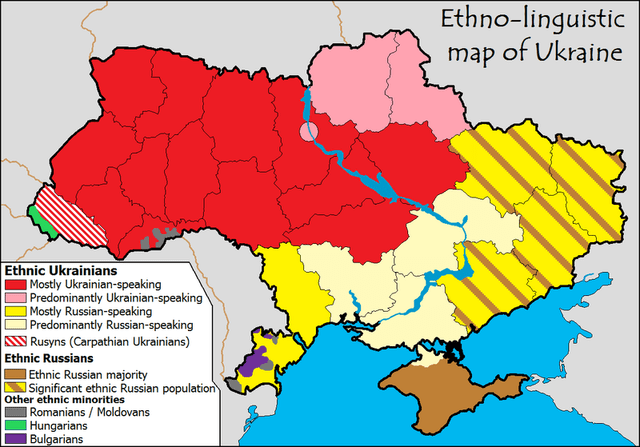

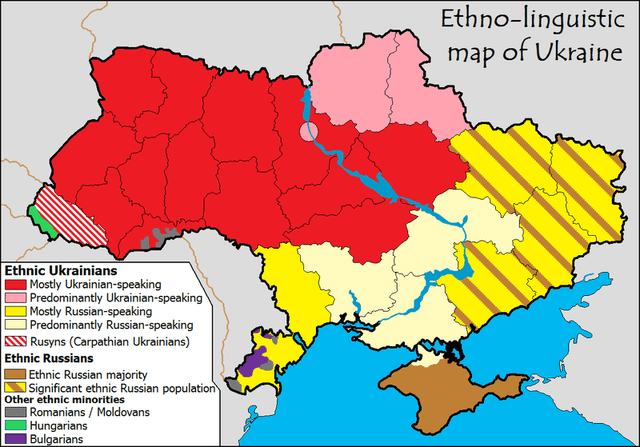

So, what’s the evidence that NATO enlargement set the stage for Russia’s invasion? Much of it’s laid out in a 2014 article by John Mearsheimer titled ‘Why the Ukraine Crisis Is the West’s Fault’. I’ll do my best to summarise. Ukraine has always been an ethnically divided country, with mostly Ukrainian speakers in the North West, and mostly Russian speakers in the South East (see above). Prior to February of 2014, about 50% of Ukrainians favoured one party, and about 50% favoured another. The map below shows results from the 2010 election. As you can see, there’s an extremely strong relationship between ethnicity and voting.

Viktor Yanukovych, whose party was favoured in the Russian-speaking parts of the country, happened to win the 2010 election. So in 2010, Ukraine had a democratically elected (albeit massively corrupt) pro-Russian President. The trouble started in November 2013, when his government decided not to ratify an association agreement with the EU so that it could pursue closer economic ties with Russia. This gave rise to the Western-backed Euromaidan protests, and the eventual toppling of Yanukovych. Which in turn led to the outbreak of the war in Donbass and Russia’s annexation of Crimea.

It would be fair to say that, prior to the toppling of Yanukovych, both the West and Russia had been meddling in Ukrainian affairs – each trying to steer the country in its own direction. After this event, however, the country veered sharply away from Russia. (This was partly due to the fact that Crimea and the Donbass – the two most pro-Russian areas – had been removed from the electoral map.)

Petro Poroshenko, the man who replaced Yanukovych, announced that “we’ve decided to return to the course of NATO integration”. NATO troops began military exercises in Ukraine later that year. Then in 2019, the Constitution was amended to include joining NATO as a strategic goal. By June of 2020, Ukraine was recognised by NATO as an “Enhanced Opportunities Partner”. And in November of 2021, the US and Ukraine signed a “Charter on Strategic Partnership”, which declared that the US “supports Ukraine’s right to decide its own future foreign policy course free from outside interference, including with respect to Ukraine’s aspirations to join NATO”.

At the same as it was making overtures to joining NATO, the government began implementing pro-nationalist policies. The day after the toppling of Yanukovych, parliament voted to repeal a 2012 law that gave Russian and other minority languages the status of “regional languages” (allowing their use in courts, schools and other public institutions). This decision was initially vetoed by the acting President. However, the law was later ruled unconstitutional by Ukraine’s Constitutional Court. Efforts to promote Ukrainian nationalism were stepped up further under Volodymyr Zelenskyy, who assumed the Presidency in 2019. He banned pro-Russian media, and arrested the opposition leader – a gentleman named Viktor Medvedchuk, who happens to be a personal friend of Putin. (Medvedchuk stands accused of treason.)

Russian leaders have long viewed Ukraine as what Mearsheimer calls a “core strategic interest”. And they have repeatedly made this clear to their counterparts in Washington. Back in 1995, when CIA Director William Burns was working at the US embassy in Moscow, he wrote a memo stating, “Hostility to early NATO expansion is almost universally felt across the domestic political spectrum here.” And in a later memo, sent to the US Secretary of State before NATO’s 2008 Bucharest Summit, Burns wrote:

Ukrainian entry into NATO is the brightest of all red lines for the Russian elite (not just Putin). In more than two and a half years of conversations with key Russian players, from knuckle-draggers in the dark recesses of the Kremlin to Putin’s sharpest liberal critics, I have yet to find anyone who views Ukraine in NATO as anything other than a direct challenge to Russian interests.

The memo was titled ‘Nyet means nyet: Russia’s NATO enlargement red lines’. Burns had previously been called in by the Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov, and reminded of Russia’s long-standing opposition to NATO membership for Ukraine. Lavrov told Burns that “the issue could potentially split the country in two, leading to violence or even, some claim, civil war, which would force Russia to decide whether to intervene.” In spite of all this, NATO members at the Bucharest Summit formally agreed that Ukraine and Georgia “will become members of NATO”.

Russian opposition to NATO membership for Ukraine is particularly strong due to feelings of betrayal over earlier rounds of NATO expansion, which they had been assured by the US would not happen. While some commentators dispute the US ever promised Russia that NATO wouldn’t expand into Eastern Europe, the political scientist Joshua Shifrinson – who has studied the issue in greater detail than anyone else – comes to different conclusions. In a prize-wining 2016 article (with 185 footnotes), he notes that

during the diplomacy surrounding German reunification in 1990, the United States repeatedly offered the Soviet Union informal assurances against NATO’s future expansion into Eastern Europe. In addition to explicit discussion of a NATO non-expansion pledge in February 1990, assurances against NATO enlargement were epitomized and encapsulated in later offers to give East Germany special military status in NATO, to construct and integrate the Soviet Union into new European security institutions, and to generally recognize Soviet interests in Eastern Europe.

Shifrinson further states, “There are numerous reasons to condemn Russian behavior in Georgia and Ukraine, as well as against states in Eastern Europe, but Russia’s leaders may be telling the truth when they claim that Russian actions are driven by mistrust.” This surely helps to explain some of Putin’s remarks in his February 22nd speech, such as when he claimed “they have deceived us” and when he referred to the US as the “empire of lies”.

Of course, there are important cultural and geographic reasons why Russian leaders regard Ukraine as a “core strategic interest”. The cultural reasons are laid out in Putin’s rambling 2015 essay ‘On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians’ – which you can read for yourself. (Note: I’m not saying Putin is correct; I realise that his factual claims are heavily contested. I’m just saying that’s what he, and probably most Russian nationalists, believe.) The geographic reasons are more straightforward: Ukraine’s vast territory provides a buffer-zone between NATO’s Western Border and Russia’s major cities; and Russia requires access to its Black Sea Fleet, which is based in the port of Sevastopol in Crimea (see above).

Finally, it’s worth noting that Putin explicitly mentioned the threat of NATO expansion as the motivation for his “special military operation” in his February 22nd speech. In fact, he spends the entire first half of the speech criticising US foreign policy vis-a-vis NATO, and arguing that NATO is an aggressive not a defensive alliance. Of course, we shouldn’t take what Putin says at face value. Perhaps he was concealing the true motivations for his military aggression? But if you’re going to make this argument, you can’t rely on other things Putin has said (like his 2015 essay), since you’ve already assumed that his words can’t be trusted.

Arguing that NATO enlargement was a key motivation for Russia’s invasion of Ukraine does not make you a “Putin apologist”. Foreign policy analysts have been pointing to the risks of NATO enlargement since before Putin came to power. And many of those analysts were bona fide American patriots (ambassadors and defence secretaries), not fringe commentators with an anti-Western axe to grind. What’s more, there’s a lot of evidence that NATO enlargement was a crucial factor in Putin’s decision-making: longstanding Russian policy with respect to Ukraine; developments in that country since 2014; and the content of Putin’s February 22nd speech.

Of course, none of this means we have to support Russia’s military aggression. So what’s the upshot? We should have followed John Mearsheimer’s advice in 2014: work with Russia to create a prosperous and neutral Ukraine, which respects minority rights. Of course, that’s no longer possible, as it’s 2022 and Russian artillery fire is raining down on Ukrainian cities. But if we want to end this conflict sooner rather than later, while minimising the risk of a devastating nuclear war, we should be pushing for some kind of settlement that accepts Ukraine won’t be a member of NATO.

No comments:

Post a Comment